1868 marked the introduction of Western influence into Japanese culture. After strictly filtering Western ships and people from entering the country, Japan opened its borders to the outside world and began receiving new ideas and technology. In particular, photography marked a transition from interpreting culture through painting and prints, to capturing it through a realistic lens that replicated real life. As a result, Ukiyo-e prints began to be used less as a way to portray realism, and more as a form of art and advertisement. The photograph, along with the new and unfamiliar presence of the West, marked a shift in Japan’s exterior image. The subjects that Japanese photographers chose were the same as those of the native arts of the late feudal period: famous places, women and actors. However their presentation was influenced by tourism (NY Times). Japanese photographers saw opportunity in selling images of traditional aesthetics and customs that were commonplace to the Japanese, but that appealed to fresh foreign eyes. This gave birth to the tourist photograph; a platform to present a stereotyped view of Japanese culture, or how it was perceived to be. Ukiyo-e prints were exoticised as well, as European collectors took delight in the “exotic” world they suggested (Merritt, 125). As seen through early photography, Japanese culture was romanticized to pander to the Western gaze. This curated Japan’s impression upon the outside world, portraying it as a traditional nation impervious to modernity rather than one rapidly developing in industrialization. “Romanticizing Japan: Contextualizing Japan Through the Western Gaze” explores the modes in which Japan was displayed -- either realistically or idealised -- for a local and global audience.

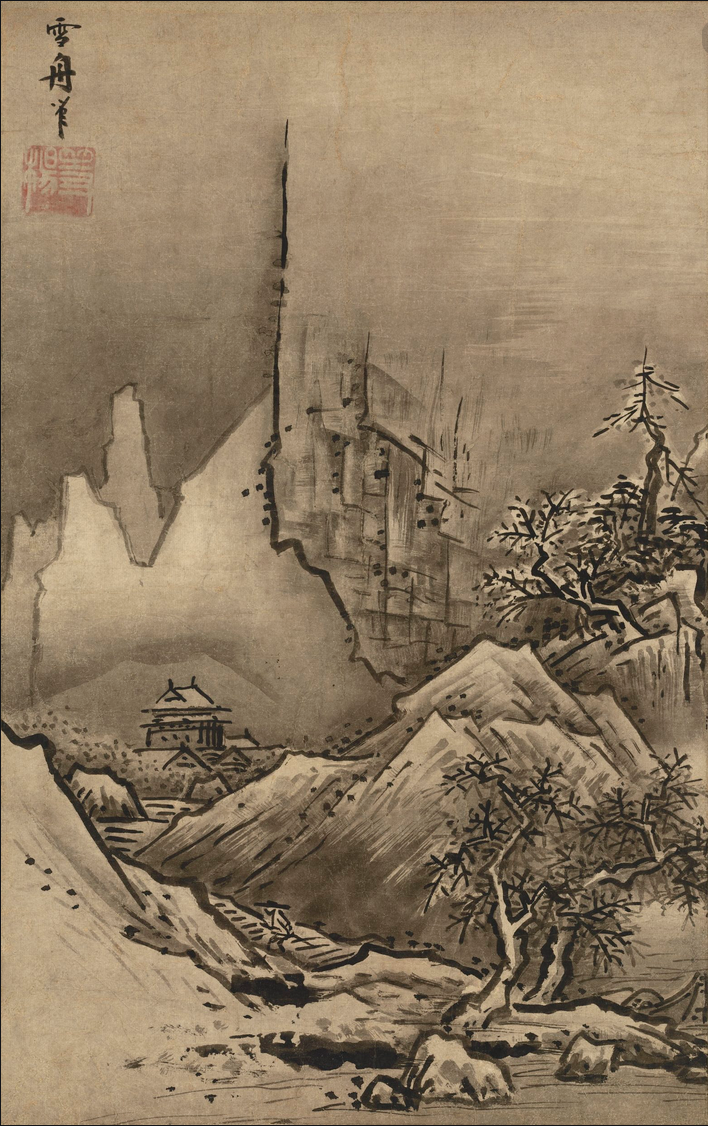

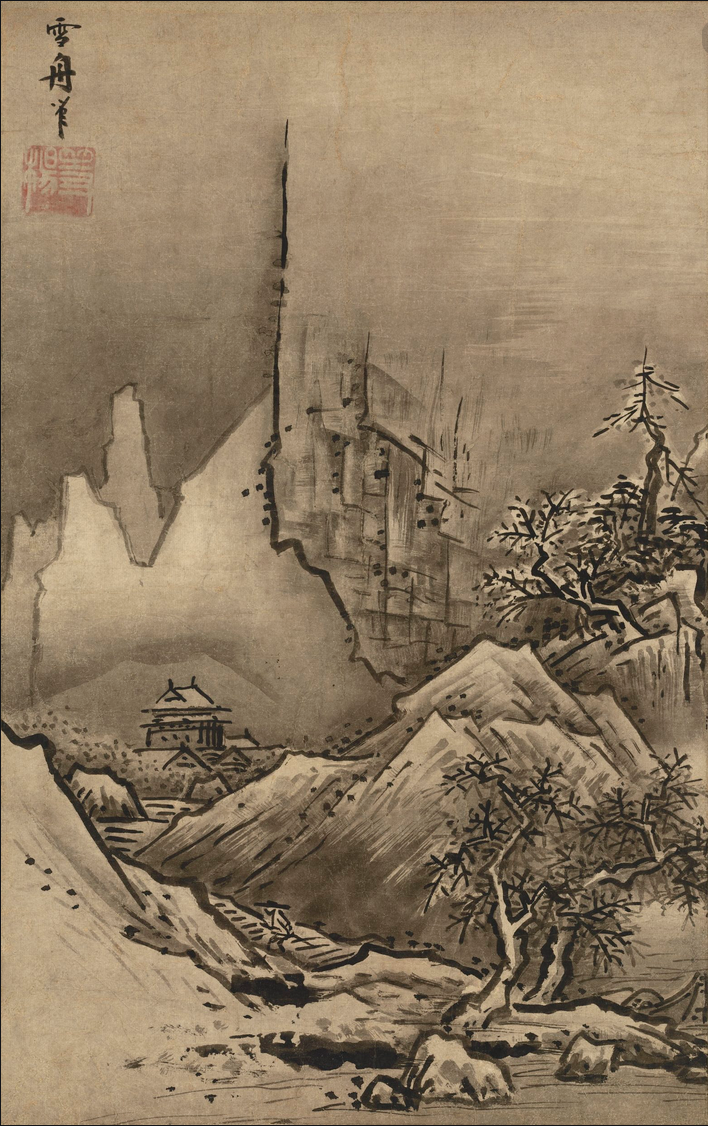

Ukiyo-e, commonly translated as “images of the floating world,” refers to Japanese woodblock prints and paintings that typically depicted interests amongst people that did not come from the ruling class during the Edo period (1603-1868). Production of ukiyo-e prints persisted during a prosperous and relatively peaceful period in Japan lasting more than 250 years, from the Edo period through the Meiji period (1868-1912). The effect of such longevity was a spectacular range of subcategories. As dye chemistry and printing techniques began to advance, the look and feel of the prints over the centuries also began to evolve, while the subject matter of the prints documented and disseminated information about changing politics, fashions, and social movements. Various authors declared the medium obsolete by the turn of the twentieth century, but the medium and production methods simply shifted in unison with western influences of modernism.

Photography first entered Japan in around 1840 by way of Dutch sea men though the port of Nagasaki and then found itself being more well-utilized by Commodore Matthew Perry’s American crew that arrived roughly a decade later. This arrival of foreigners and ultimately foreign art was in particular unique to Japan, in that photography was able to evolve and document the vast changes the country went through before, during, and after the Meiji Period or Restoration (1868-1912). Photography, though originally by the Japanese government for military and survey purposes, soon became a tool that simultaneously represented and challenged the previous traditional and then current modern identities of the nation. Tourist photography, in particular, encapsulated a traditional East Asain culture that had been hidden from Western foreigner audiences while Japan had existed in isolation since the 1630s. This exocitisized and manufactured product grew its own market, and within years photography studios popped up all around the country’s international ports selling views (landscapes, cityscapes, and architectural scenes) and types (genre scenes posed on location or in the photographer’s studio) that have become iconic to the “image” of Japan to this day.